The concept of risk appetite and tolerance is commonly referred to in today’s volatile and unpredictable business environment. Based on my conversations with multiple businesses over the last several months I’ve found that it is a widely understood, but often misapplied concept. I was working with a client recently to assess whether the residual risk in the current control environment was within the enterprise risk appetite levels. Due to some recent market shifts, the board of this company had made some significant changes to their risk appetite guidance. The guidance was expectedly very high level because of course, that’s what the board does, but how could we take that high level guidance down to a view where control owners can determine if they are within the appetite guidance? This is a systemic problem for most of us. Deciphering high level risk appetite statements is sometimes difficult to begin with but failure to have mechanisms in place to translate that guidance into decision making at the operational level can be one of your biggest vulnerabilities.

What is risk appetite?

Each organization has their own objectives intended to create value for its stakeholders and should broadly understand the risk it is willing to undertake in doing so. Therefore, the risk appetite statement is an expression of the amount and type of risk that an enterprise is willing to accept in the pursuit of its business goals. Organizations should have a framework that provides an approach to the management, measurement, and control of risk.

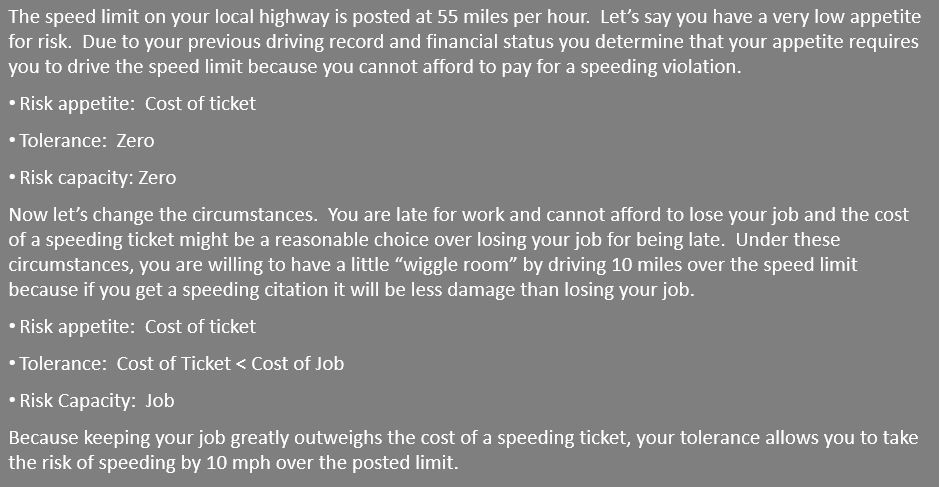

Oftentimes, risk appetite is used interchangeably with risk tolerance and risk capacity. Although they are related it is important to understand the key differences. Tolerance differs from appetite in that it defines the acceptable level of deviation, or what I call the “wiggle room” under certain circumstances. Capacity, on the other hand, is the objective amount of loss that an enterprise can tolerate without risking its continued existence. It differs from risk appetite which is more high level.

I was recently talking with a colleague of mine, Ed McCabe (Linked-In Profile) about this subject. My question to Ed was this: “Why is the whole concept of risk appetite largely misunderstood at many companies?” His response, not surprisingly was this: “Normally it falls into one of three reasons. First, organization’s don’t want to think about it – they focus on ‘what they’ll win’ rather what they’re betting with, what they could potentially lose if things don’t fall inline. Second, organizations aren’t investing the time to define and communicate a clear understanding of how they are defining these levels. All too often I see Boards and Senior Management use a scaled system of High, Medium and Low, but they don’t actually define what those are for their staff. What’s “High” to a system administrator sitting behind a console isn’t going to be “High” for the CIO or CFO. Finally, one of the last things that I’ve seen is that no one has taken the time to simply ask the question or effectively communicate what the risk appetite and tolerance criteria actually is. We live in a very volatile and dynamic business world, one in which our risk appetite and tolerances are going to change – it falls on us to seek out the proper definitions for these. If you struggle getting those answers, then I suggest start with the absurd and then let Senior Management respond accordingly so we can then adjust and gain that clarity and definition.”

Based on his input, we agreed on a simple analogy to help put these three definitions into perspective:

Looking at appetite from different views.

Appetite statements often start out broadly with a single high level statement followed by more detailed statements that cascade down to different levels of the organization. Some organizations find that broad statements such as “low,” “medium,” or “high” appetite are suitable for their needs but this largely depends on your culture and organizational structures. The higher you are in an enterprise, the more vague the guidance appears. Logically, the lower you go, the more specific the guidance should be. There is no right appetite that applies to all organizations; however, there is an appetite suitable for each organization that can be interpreted and used at all decision levels. How do we take a high level appetite statement from the board and apply it to the level in which we are working and trying to make decisions? In the case of the client I was working with, they chose looking at appetite from three views, or what they called altitudes: strategic, tactical and operational.

Strategic Altitude

The risk appetite at this level should clarify the nature of acceptable risk and provide confidence that the organization remains aligned with its overall mission and vision. This is generally considered the highest level of the organization such as the governing body and/or executive management.

At the strategic altitude, risk appetite is driven by many factors such as mission, vision, values and of course the strategic direction of the enterprise. For example, if an organization’s strategy assumes its industry will undergo significant disruption from digital transformation it may see the need for a higher appetite to be innovative and successful in the market.

Strategic categories may relate to growth, efficiency, customer or innovation (you may recognize the four dimensions of the balanced scorecard here). More progressive organizations may also consider corporate responsibilities in the social, environmental and diversity areas as well. These are typically set out in a strategic plan or an annual report. Most often, there are very few categories at this level. Below is an example of an enterprise’s stated strategy and possible appetite statements.

Tactical Altitude

Below the strategic view comes the tactical view. This is generally the business unit level. I would also include areas such as finance, IT, HR, etc. This is an important link between the highest level of appetite and what I call the “street view.”

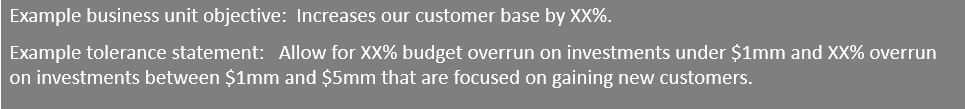

This altitude takes the strategic risk appetite statement and transitions this into more specific guidance based on the objectives of that business unit. Not only will the tactical altitude determine more specific appetite, but here is where I now insert risk tolerance and capacity clarity. Tolerance is more specific and provides insight into decisions made within the business unit decision making structure. Unlike the broad risk appetite, tolerance is tactical and focused. Ideally, the tolerance guidance should apply to specific business unit objectives, should support the overall strategic appetite statement, easily understood and cascaded down to the operational level for risk-based decision making.

When determining tolerance, the business unit considers the overall enterprise appetite and how it applies to the relevance of each objective where the highest ranked objectives may have lower risk tolerance levels. As discussed earlier, tolerance is the acceptable level of deviation for any particular risk. At this altitude, resources become a major consideration as well, where you may assign more resources to areas with lower tolerance levels. Below is an example of a tactical level (business unit) tolerance statement based on the organization’s appetite.

Operational Altitude:

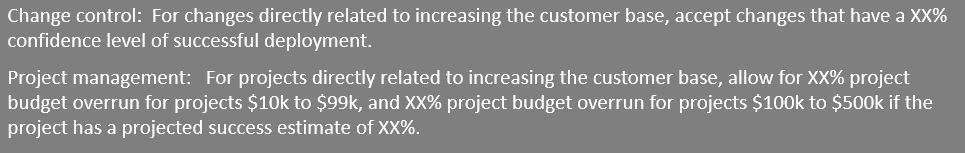

This view is focused on performance, or what I called the “street view” earlier in this blog because this is where the work gets done and decisions have to be made to deliver products and services. At this view, questions such as “How much risk can I take to achieve an objective?” must be considered. Performance achievement can identify whether the organization is, or is not assuming enough risk to achieve the desired objectives. Therefore, this is the place where the balance between risk and performance is determined. A question I often ask decision makers at this altitude is this: “How do you know that the decision you are about to make is within 1) your level of authority and 2) within the appetite and tolerance levels of the enterprise?”

Views regarding performance often vary within the organization. Management should not assume that operational leaders have the guidance they need to make decisions within the intended appetite. It has been my experience that in many cases they simply don’t know what that appetite is, so they are making decisions blindly. Therefore, organizations need to review the application of appetite through other practices. This can be done through an effective monitoring and communication plan, which is up next. Let’s say your organization has effectively identified and communicated risk appetite and tolerance levels throughout all of these altitudes. If so, you may have statements that look something like the following:

Communicating risk appetite.

Having a cascading appetite and tolerance mechanism sounds great, but it is useless if you don’t communicate this information throughout the enterprise which allows for all altitudes to make appropriate and informed risk based decisions that are within the defined appetite and tolerance levels.

Of course, communication mechanisms vary based on the culture and structure of each organization. To get some clarity on this, I reached out to Robin “Montana” Williams (https://www.linkedin.com/in/robin-montana-williams-88b8a024/) to get his suggestions on how to communicate appetite and tolerance throughout the organization, and he offered me some great advice: “The communication of clear and defined appetite parameters that an organization will take in pursuit of its business objectives, and the tolerance acceptable variation in the performance measures linked to organizations business objectives must be understood across the organization—from the boardroom to the breakroom.”

Communication channels should be open and easily implemented so that all altitudes are up to date on organizational risk information. Lower altitude employees tend to focus on specific limits defined in risk tolerance as opposed to the high-level strategic objectives and how they are aligned with risk-taking, so ensure that you are tailoring risk communications based on the point of view.

It is also very important for your audit and assurance function to be aware of appetite and tolerance. Audit scopes their efforts from a risk-based perspective and can use this information to gain insight on what the organization and stakeholders consider their highest risks. Not wanting to leave audit out of this, I reached out to Mary Akers (Linked in link) for her audit input on this blog: “An organization can have all of the right frameworks, policies and procedures documented and still not effectively communicate. An organization’s culture as well as unclear directives of departments such as Compliance, Risk Management, and Assurance/Audit has a significant impact on the critical information that ends up in all forms of communications to include status reports and matrices, whatever methodology is utilized.”

When the organization’s emphasis on meeting budgets, employee performance assessments, and deadlines become more important than meeting business requirements, communications will naturally be overly optimistic; even those projects that are reportedly in red status. Important attributes and critical controls will be overlooked. Why? Because the organization’s tolerance and capacity are not aligned with risk appetite culturally and practically. Assess what is documented with what is actually occurring in practice. Don’t let the external auditor/examiner or hacktivist be the first to tell you that you have communication issues which end up with far more adverse consequences such as financial and reputational impacts.

Based on my research and experience, I can summarize that effective communication strategies should have the following attributes:

- Statements should be clear, understandable and stated in a way that assists decision making

- Statements should be applied and cascaded through all altitudes of the organization

- Statements should be documented through policies and procedures

- Statements should be adjusted and communicated as internal and external factors change the enterprise’s risk profile

Mark’s top tips.

I normally have a lot of my own tips and tricks in my blogs, but since I reached out to several colleagues for their input, I thought it was best to get their tips for this closing.

Mark’s top tip: Integrate risk appetite, tolerance and capacity statements with all decision making levels in the organization. As discussed in this blog, start with a strategic, tactical and operational view and add/remove “altitudes” as your organization sees fit and adjust your appetite position as your environment changes.

Ed’s top tip: Take the time to ask and answer the hard risk appetite and tolerance questions, for the pessimists this means asking “How much am I willing to lose?” for the optimists “How much am I willing to bet that we’ll succeed?” Whether you’re a pessimist or optimist, ask the question until you get a sufficient answer. Too often I see organizations that don’t effectively communicate the risk appetite and this results in a lot of time and effort spent on attempting to engineer for solutions that otherwise should be accepted and not focusing efforts where they really should be – those risks which exceed the defined risk appetite.

Montana’s top tip: Maintaining consistent understanding, implementation, and monitoring of appetite and tolerance is the key to achieving the desired outcomes that enable attaining organizational objectives.

Mary’s top tip: Do your homework and read the engagement risk appetite, tolerance, and capacity statements. Don’t simply ask management, “what keeps you up at night?”

As always, your thoughts and reactions are welcomed!