DON’T WAIT FOR A RISK EVENT TO HAPPEN BEFORE YOU ADDRESS YOUR ENTERPRISE RISKS.

As I write this blog, I am experiencing a business disruption, and it is very frustrating. Should I blame my vendor, or is it my fault for not effectively managing my business risks?

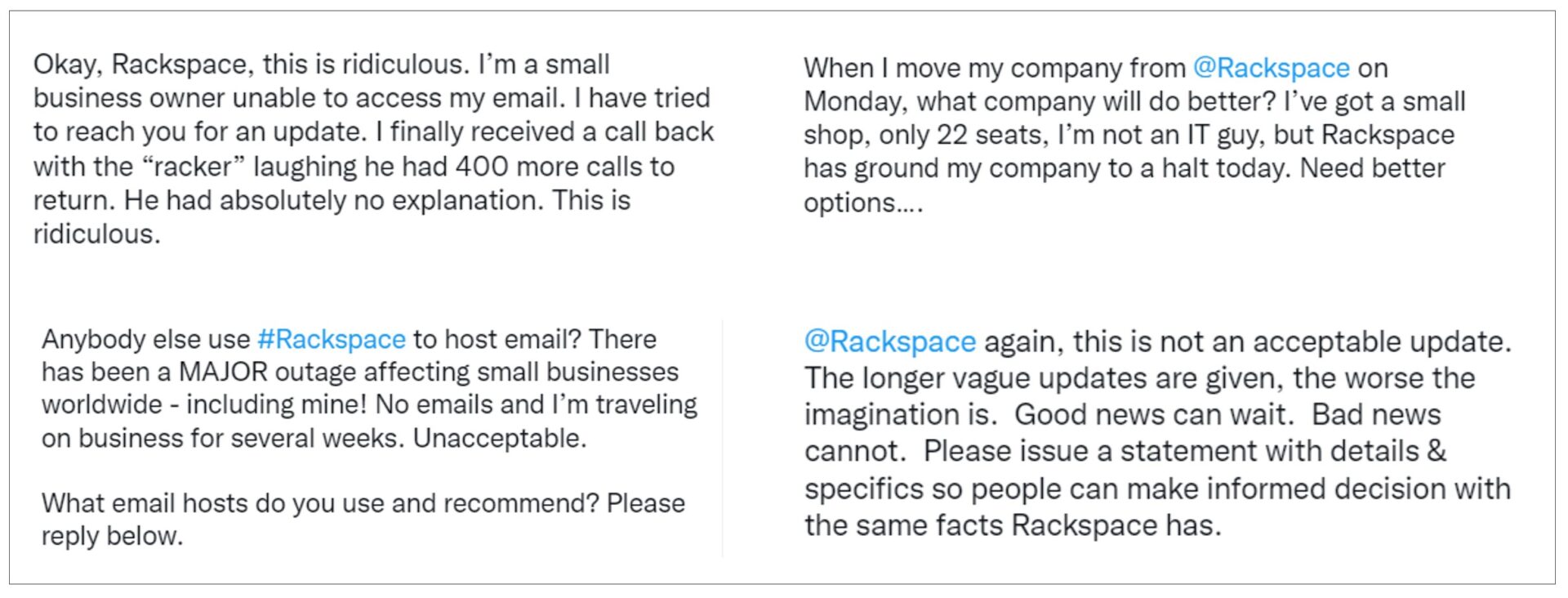

I outsource my email and my provider has been down for several days with no end in sight. In fact, it took them several hours to even fess up to this event, and when they finally did, the communication was dismal at best. If you don’t use Rackspace for your email, you most likely haven’t heard about this massive outage. If you do, you are probably shaking your head while you read this.

Like most businesses, especially small entities like mine, we outsource many of our processes. We outsource IT services, payroll, testing, recruiting, development, websites, and many others. However, I can’t think of a single company like mine who doesn’t outsource their email. Small to medium sized enterprises depend on it. When I was working in large enterprises, I used to always joke about email. My theory was that email wasn’t considered a critical service until it went down. Well, it did for my business, and as it turns out…yes, it is a critical service. But I had a backup plan because I considered my risks, but did I do enough to predict this?

I don’t mean to beat down Rackspace while they’re down, but here’s my perspective from a customer/user perspective. Today is Monday, and this event started on Friday. I still have no clue what is going on. Rackspace is a $3B company who has recently chosen to ship its “Fanatical” customer service elsewhere as well as conducing several layoffs in recent memory. I’m not saying these are root causes, but I certainly should have seen these as potential risks. I’ve seen their service management practices decay in the last several months, but still considered any risk scenario with Rackspace as low likelihood because of their history with me.

If you do a quick search on Twitter, you’ll see some VERY irritated customers:

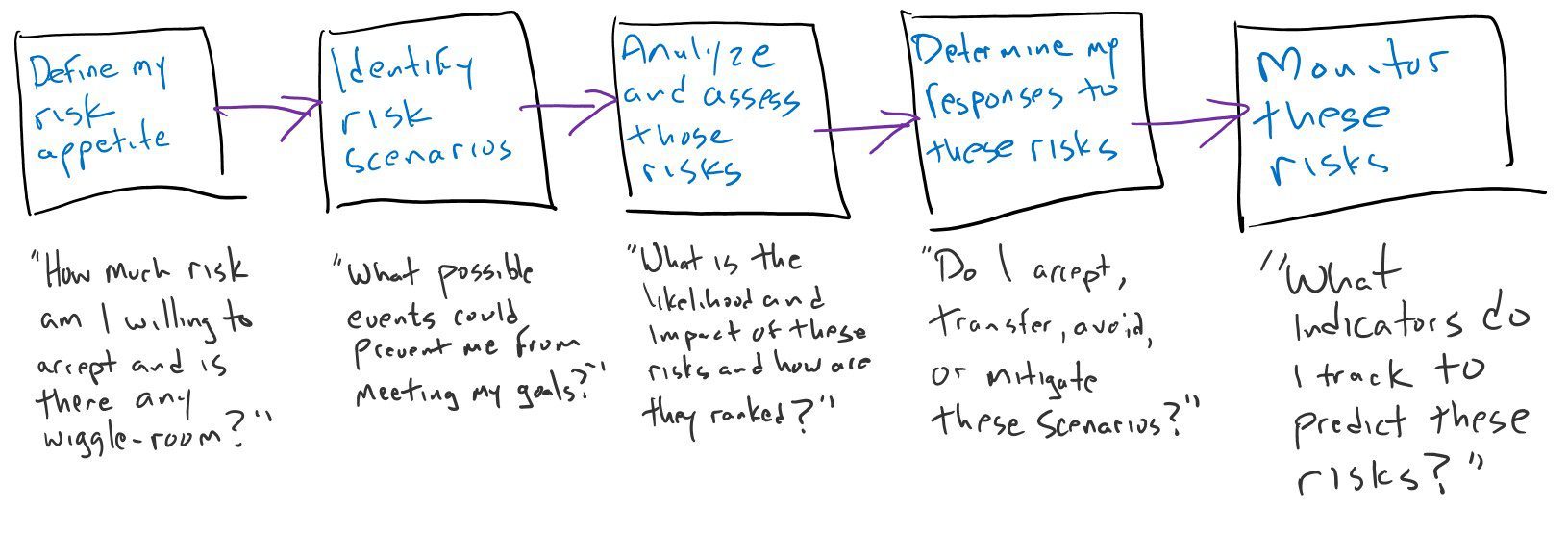

Let’s link this whole situation to risk. As a business owner, I think about those risks that could prevent my business from achieving its objectives. I continually think about the risk management process when it comes to my business. For your reference, the following is a quick view of the risk process I use:

Let’s dive into how I was somewhat prepared for this risk event. Using my risk management process from above, I want to break down my thinking for you.

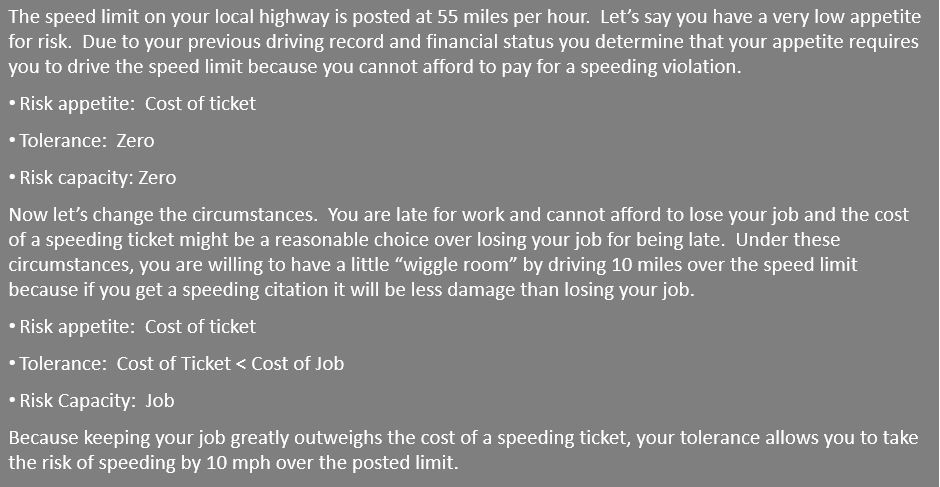

Step 1, Identify my risk appetite.

Risk appetite is defined as the amount of risk I am willing to accept in pursuit of my goals, where tolerance is the acceptable level of deviation, or what I call the “wiggle room” under certain circumstances. What is my risk appetite and tolerance with respect to client communications?

“I will not accept a risk scenario that prevents me from communicating with my clients for more that three days. I will have a limited amount of tolerance during weekends, holidays and times of low project reporting times as long as it does not affect project deliverables.”

Now, let’s see how this drives the next several risk management steps.

Step 2, identify risk scenarios.

Think about the events that could happen that would impede your progress. As a small business owner, you can use several techniques to do this such as identifying previous events, scan current newsworthy events and industry articles, brainstorming, and identifying all scenarios that could possibly prevent you from meeting your goals.

For me, these include the following three high level scenarios:

An event that could prevent me from traveling, because travel is key to me delivering many of my engagements and courses.

An event that could prevent me from sharing knowledge online because I’m in the business of sharing knowledge with clients and peers.

An event that could prevent me from communicating with my clients, suppliers, and peers, because this is required for me to contract, execute and close projects with my clients.

An event that might affect my standing in the GRC community.

Therefore, examples of my key risk scenarios include:

Power, internet, or telco outage

Sickness or illness

Disruption in the travel industry

Failure to stay on top of the latest trends in GRC

A contractual or legal matter

Step 3, Analyze and assess risk scenarios.

This sounds easy, but it takes a little thought. For each of the scenarios that I discovered in step 2, I had to come up with a way to prioritize these. I went with the basic X and Y grid using X for likelihood and Y for impact.

Imagine a grid that visualizes this. You can use any form of measurement for this, like Low-Med-High, or a numerical system to meet your needs. Something like this:

Likelihood identifies the ‘chances’ the risk event could happen. It is based on frequency, probability, vulnerability and event timing. Impact is very different. It looks at things like goals achievement, financial, reputational, compliance, safety, privacy, and security impacts.

Once I identified these risks and analyzed their impact and likelihood, I prioritized these risks. It comes as no surprise that “power, internet, or telco outage” was high on my list. I’m also assuming that an email outage is part of this.

Step 4, Determine responses to those scenarios.

Now that I had a prioritized list of risks to my business, what should I do? I’ll boil this down to four primary responses:

I can choose to simply accept the risk.

This is not an option. Accepting a risk means that if the risk event becomes real, there’s no effect on my business. Accepting a risk basically means that if it happens, the effects are within my risk appetite and tolerance levels. Pass on this option since it exceeds my risk appetite.

I can choose to avoid the risk.

Avoidance in this case means that I choose to not use email at all, therefore avoiding the risk of this affecting my business. I choose to pass on this option as well because I, and many of my clients, depend on this communication medium.

Additionally, there are cost effective responses I can put in place to reduce either the likelihood or impact within my appetite level.

I can choose to transfer the risk.

Of course, the typical answer to this is insurance or outsourcing. Well, I outsourced this, but there is still the possibility of third party or vendor risk. What if my outsourcer fails? Yep, that happened. Let’s move to mitigation.

I can choose to mitigate the risk.

As luck would have it. I chose to mitigate this risk. Things that were going through my mind were things exactly like what is happening right now: what if my outsourcer fails to deliver on our agreement?

Here are my mitigations:

Create alternative email addresses to use in case my vendor fails

Use social media to communicate the change in my status

Have multiple sources of internet including phone hotspot and internet hotspot from a different provider

Step 5, Monitor these risk scenarios and continuously update my risks.

Here is the tough part, and frankly where I failed. For each risk, it is key to create some indicators that tells you whether the risk likelihood is low or high. Think of this as the weather report. If inclement weather affects your business, then you watch the weather forecast to determine how you might approach your day. As with any risk, what are the indicators you look to for indications that the risk event might become real? I’ll be honest, I failed at watching any key risk indicators for Rackspace. Had I done this, I would have had the information I needed to move away from this high-risk relationship before the risk event happened.

What I’ve leaned from this event? Digital Trust. You’ve no doubt seen some of my recent social media posts on digital trust. I’ve been a customer of organizations who have experienced situations like this in the past, but I stayed with them. Take for example a major hotel chain that has experienced several reportable breaches, yet I’m still a loyal customer of theirs. Why is it that Rackspace has one event, and I’m ready to leave them? That is digital trust. Stay tuned, I’ll be posting a blog on digital trust very soon.

As always, I look forward to your comments.

Recent Comments